|

Walter Spies

A young Bainese Legong dancer from Bedulu, 1936. |

Walter Spies came to Indonesia in 1923 in search of a more genuine and satisfying existence than that he had previously experienced in Germany in the five years following World War I.

Born in Moscow in 1895 into a well-to-do German family with wide-ranging business interests, he grew up fluent in both German and Russian and was trained to regard the German tradition as one of intellectual, analytic thought, while his experience of Russia was of the worlds of nature and art. From 1905, winter meant academic schooling in Dresden; summer meant long holidays on a family estate at Nekljudovo in the Russian countryside. At the time, photography meant formal studio portraits of the family, but also snapshots of tennis parties and pet animals. With the coming of the war, the family was scattered and its Russian fortune confiscated.

Spies spent three years in rustic internment at Sterlitamak in the southern Urals, living and studying the life of the semi-nomadic Bashkir, Kirgiz and Tartar tribes of the region. During the post-revolutionary turmoil, he made his way back to civilization. For some months he enjoyed the euphoric, experimental liberation of the artistic life of Moscow, when painters like Marc Chagall and Wassily Kandinsky came back to Russia to celebrate the dawn of a new age. But when life became dangerous for foreigners, he had to return to Germany and the penurious existence of the bohemian artist in Dresden and Berlin whose one rule in life was never to commit oneself to a system.

While he never received any formal painting instruction, Spies picked up many features of his later painting style from his friends Otto Dix and Oskar Kokoschka. At the time of their closest contact, Dix was making an intense study of the techniques of applying glazes characteristic of the Old Masters and using this knowledge in his own work. Spies adopted this method as his favored medium. The contact with Kokoschka was more personal than professional. Many people who knew Spies have spoken of the charm and grace of his personality; perhaps it was not just typical hyperbole when Kokoschka wrote of him that "when he left die room it was as if the sun went down."1

As a member of the Berlin avant-garde in painting and music circles in 1920, it was inevitable that Spies should come into contact with the world of film. A close friendship developed with Friedrich Murnau, and Spies acted as artistic adviser for a number of Murnau's major silent films, the best known being Nosferatu, the vampire film. It was no doubt his close observation and discussion of Murnau's filming techniques that taught Spies how to use dramatic lighting effects and unusual perspectives, stylistic devices he continued to use in his paintings and in the films he later helped others to make in Indonesia. Two dominant features of his painting style that may be traced to this early work on the film under Murnau are the compositional device of strongly emphasized diagonals and the concentration on tonal contrast rather than vivid color.

The failure of German society to achieve a new, viable and stable form in the post-war years, and its retreat into conservatism led many intellectuals and artists to emigrate, either physically or spiritually. Spies found himself stifled in the tense atmosphere of Berlin and talked more and more frequently of leaving. As a result of having made good friends in Holland with colonial connections, he laid careful plans to test life in what was then the Dutch East Indies. The initial impetus behind his decision perhaps stemmed from his discovery in Berlin of Gregor Krause's book of photographs celebrating Bali and its people.

After working his passage to Java as an ordinary seaman on a collier, it was not long before Spies found a position as director of the Western orchestra of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, a job that gave time for painting and access to the study of the Court Arts, including the instruments and music of the Javanese gamelan. Surviving prints in family albums from this time show that Spies used photography as an aide-memoire for landscape paintings, and his photographs reflected the rhythmic repetition of forms such as the lattice of a bamboo suspension bridge, or fixed the framed space of a body of water seen through surrounding foliage.

In 1927 he exchanged the delicacy and refinement of the Central Javanese court for the robustness and vigour of Bali. After several visits there, he moved to the upland village of Ubud at the invitation of the local ruler, Cokorda Gede Rake Sukawati. For twelve years, Spies seldom left Bali, steeping himself in the arts, customs and history of its people and becoming familiar with every facet of its physical nature. The discoveries he made found expression in paintings and drawings, films and gramaphone records, articles in learned journals and guide books.

The greater part of his photographic records and written manuscript studies was lost when he was interned, again as a German national, during World War II. Eighteen months later, in January 1942, he met his death by drowning when the S. S. Van Imhofif, taking internees to British India, was sunk by a Japanese bomber off the coast of the island of Nias. In spite of the efforts by friends to preserve them, most of his papers and possessions disappeared during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia.

Nevertheless, the Dutch scholarly journals of the twenties and thirties bear more than a few of Spies' photographs of archeological and ethnographic subjects. His first camera was a Rolleiflex, which came to grief by tumbling down a gorge in Sumatra when Spies was scrambling over rocks in pursuit of a butterfly. This was soon replaced in late 1935 by the newest Leica, received from Victor Baron von Plessen as a partial payment for his work on the film Inselder Demonen (Black Magic), which had been shot, largely under Spies' direction, in 1931.

Most photographs presented here were made during 1936 as illustrations for the book Dance and Drama in Bali which he wrote in collaboration with Beryl de Zoere, a British expert on dance. Over one hundred photographs by Spies were included in thar publication, and most of the original prints, along with others that were not used, were preserved when Beryl de Zoete took them to London. They eventually found their way to the Leiden University. As photographs of the dance, they fall naturally into several groups, according to the kinds of dance portrayed; but these groups also rather neatly illustrate the subjects, themes or concerns that moved Spies, both as a visual artist and as a musician.

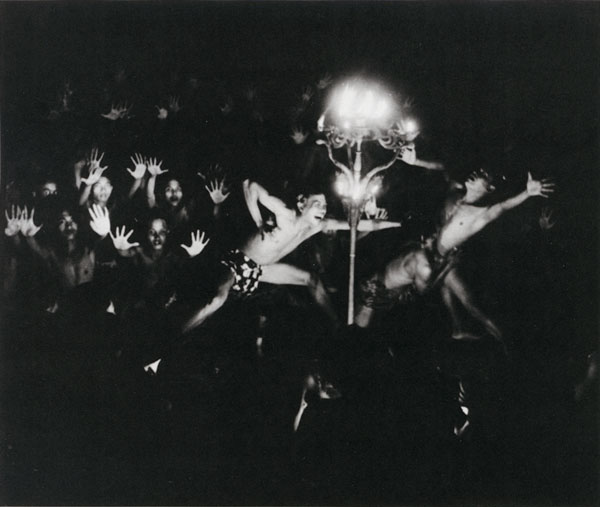

It is in dancing above all that patterns of space and time come together. We can here discern the straight descriptive element of the portrait; whether of Mario of Tabanan, creator of the Kebyar, in a pose from this seated flirtation dance, which apparently defies gravity in its folds and angles; or of the classical Legong dancer from Bedulu, where curve echoes curve; or again of the simultaneous relaxation and tension of the hobby-horse dancer in trance.

Another group involves dancers in formation, such as in the Baris (warrior) dances or in the Rejangtempk dances. Repetitive patterning held a great fascination for Spies throughout his life, whether in music or the visual arts. For example, he found it perfectly natural that there was an underlying unity connecting the music of Johann Sebastian Bach, the gamelan, the wing of a dragonfly and growth patterns of foliage, and he constantly returned to the question of how delight in the discovery of pattern in one sphere could find its echo in another.

He drew and photographed the rhythmic ornament of Balinese palm-leaf banners (lamak) and the ebulliently florid carvings in wood and stone. When Balinese painters in the early thirties started producing a new style of wotk, there was a marked emphasis in work by painters from around Ubud, who were Spies' friends, on the rhythmic treatment of natural forms.

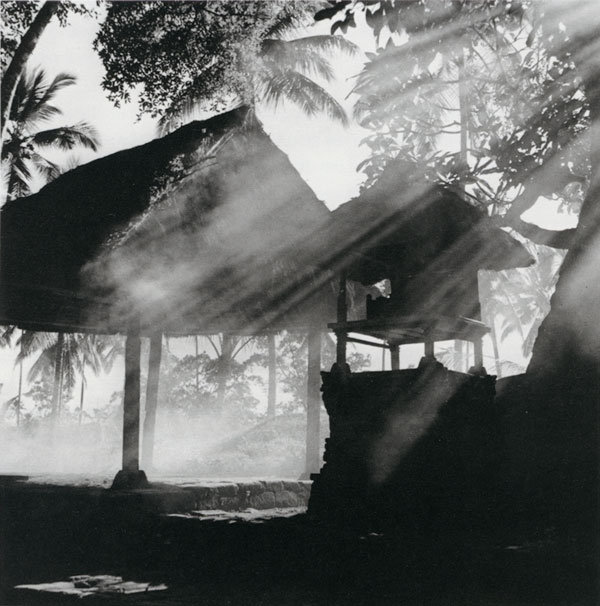

The third group of photographs depicts figures in a landscape, often dramatically back-lit, such as the Rangdas from the Barongplzy. The feeling for the theatrical that pervades Spies' view of Bali is displayed in the photograph taken in early morning light of the village of Trunyan on the shores of Lake Batur, where he had come to record a fertility ceremony. Light slants through the trees and across both the roofs of the hall and the throne for the gods on its pedestal on the righthand side. The roofs of these structures are in shadow and cast their own deep shadows, so that the brightly lit area behind is like a stage or screen awaiting some drama soon to be enacted.

We can readily observe that the early impulse from the films of Friedrich Murnau found one echo in the tonal contrast between deep jungle shadow and bright tropical sunlight of the Balinese landscape and another in the "moving pictures" of the wayang kulit, the Indonesian shadow puppet play; all of them contribute to the specific quality of the painter's style. There is an irony in the fact that Spies' surviving paintings are scattered around the world, most of them in private collections and thus not readily accessible. His public reputation as an artist rests to a great extent on the photographs in Dance and Drama, which were so carefully printed to his specifications.

During the thirties, photography was rapidly developing as a tool for the anthropologist, and it was Gregory Bateson and Margaret Mead who took photographic recording of the subjects of their field work to its limits. During their period in Bali from 1936 to 1938, they sometimes photographed the same performances and ceremonies that Spies had arranged to record for his book. When Dance and Drama was finished, Spies passed his camera to the anthropologists' colleague, Jane Belo, who was recording children and trance-dancers.

Her husband, Colin McPhee, a musicologist and composer, was also a fine photographer with a great sense for rendering volumes. This group of artist-scholar-scientists compiled an impressive photographic account of Bali between the Wars, but for Spies, every record required transformation through the operation of aesthetic vision. He was above all a picture maker.

This is the way he was remembered by a friend from the Dutch colonial administration:... the picture that springs to mind is that of the photographer I so often saw in the mornings on our trips to the highlands. As we sat outside our tent, usually placed to take advantage of a good view... he would suddenly seize his Rolleiflex and go off without saying a word to photograph the mists gleaming in the first light or smoke rising from the houses in the valley. I can still see his face before me as he watched with attention keyed to catch the awakening daily round of the village or the gentle sway of a cluster of giant bamboo stems overhanging a gorge. Incidentally this was an expression he habitually adopted when pacing around a subject he was about to photograph, muttering away to himself in concentration.2

NOTES

- From a memoir by Kokoschka in Hans Rhodius, Schonheit und Reichtum des lebens, Walter Spies, Maler und Musiker auf Bali, [895-19 '',,Boucher, Den Haag, 1964, 119.

- Ibid., Memoir by C. J. Grader, 357.

|

Walter Spies

Altar and pavilion in Trunyan village, on the shore of Lake Batur, Bali 1932. |

|

Walter Spies

Rangdas from the Barong play at Pagoetan, Bali, 1937. |

|

Walter Spies

Kechak dancers in a village purification ceremony, Bali, 1936. |

|

Walter Spies

Balinese women at Tenganan dancing the Rejang, 1936. |

|

Walter Spies

Mario, the legendary Balinese dancer, performing the Kebyar, 1936. |

|

Walter Spies

Barong Landung, a protective spirit periodically brought out of the temple, Bali, 1936. |

| next paper | about John Stowell

| contents page | asia-pacific photography | photo-web | contacts

|