|

Tassilo Adam

Courtiers of the Sultanate of Paku Alam holding royal insignia, Yogyakarta, 1924 |

In August 1944, Tassilo Adam donated a portion of his invaluable collection of photographs of the Batak people and other Sumatran ethnic groups, together with a complete documentation of central Javanese dance, to the Royal Tropical Institute in Amsterdam.

Despite the fact that Adam had no formal training as an ethnologist, his approach to photography, and later to filmmaking, resembled that of an ethnologist, and the work he had done for the Dutch East Indies Government was valued as such. The collection spans fourteen years, from 1912 to 1926, and his Batak photographs, which had been registered at the museum in 1919, attest to his acute eye and thorough observations. It is clear from his photographs that Adam was infused with an appreciation and understanding of the Indonesian people he lived among for more than twenty-five years.

Born in Munich in 1878 to the German painter Emil Adam and an Italian mother, Tassilo Adam was destined to move to more distant and exotic shores during his seventy-seven year lifetime. Adam left Munich for further studies in Vienna at the tender age of sixteen. While still in Vienna in 1898, according to Adam's daughter-in-law, Elanore, he read a book about the Batak people of Sumatra.

Fascinated by its contents, the adventuresome youth immediately decided to go there. The following year, at the age of twenty-one, Adam left Vienna to work on a Dutch tobacco plantation in Deli, near Medan, on the island of Sumatra.

Adam's stay in the Dutch East Indies was punctuated with severe bouts of malaria, among other serious tropical diseases. In "A Personal Experience with Malaria," published in the Knickerbocker Weekly, December 27,1943, he recounted how he had resorted to a Sumatran herb mixture as a cure for dengue fever. In fact, it was out of concern for his health that Adam took sick leave and returned to Vienna in 1912; during this short trip he met and married Johanna. After returning to Sumatra with his bride, his health remained precarious, and he became adept at using traditional herb cures.

Tassilo Adam started to photograph when he came back to Sumatra, setting up a darkroom in his home in Pematangsiantar in 1914 and processing his prints himself. Due to the tropical temperatures, he had to resort to using buckets of ice to cool the water used when developing. Adam recorded much pictorial information about the ethnic group of the Kubus. He also spent some time researching the life of the inhabitants of Nias Island, off the coast of Sumatra. During his time in Sumatra, he collected many Batak artifacts, which he sent back to Dutch museums as a part of his ethnological work. Adam learned the Batak language; and, in 1948, he wrote the first book on Malay-Batak grammar with James Butler.

Once his studio was in place, what followed for Tassilo Adam was a very fertile period of photographic and ethnological research of Batak customs and physical surroundings, in particular those of the Karo Bataks. In addition to his photographic documentation, Adam recorded his impressions in writing; and, according to his observations, the Batak lived in constant fear for their tendi, or soul, the double of the ego, which was continually threatened by the begus, or evil spirits. Not only humans, but every living thing, including certain plants, had tendis. This was especially true of rice, their chief food.

Basically a mystic who sympathized greatly with the Bataks, respected their culture and cared about the people, Adam did not have a typical "colonial" attitude. Perhaps it was this direct approach that contributed to the ease with which he gained the confidence of those he photographed. His portraits are of proud Batak personalities looking into the camera with admirable poise.

Adam became good friends with Pa Melga, the sibajak, of chief, of the large Karo Batak village of Kaban Djahe. One day he was invited to a great festival at Pa Melga's home at which evil spirits would be captured by a sibasso, a spirit-medium priestess. When she went into a trance, the photographer was ready: "My camera was set. A large amount of powder, which was necessary for a good picture, had been provided. But since it had become wet, I used a bamboo five meters long, attached to a cotton pad dipped in alcohol, to explode it. I shot six times so that the whole house trembled.

It was a dangerous experiment; at each shot I fully expected to see flames."1 One print shows the priestess, eyes closed and apparently in a deep trance, facing the photographer with the intense faces of seated villagers surrounding her.

One difficulty Adam faced was the Bataks' fear that by being photographed their tendis could be endangered. In one case, much to Adam's surprise and horror, a chieftain died three days after having refused to let Adam take his portrait, at which time Adam had said jokingly that he would get him dead or alive. Another time, a portrait he made of only the head of a chieftain of a headhunter tribe almost led to his own death. It was only when he returned with a full-length portrait that the chieftain was certain of getting his body back, and consequently the photographer was out of danger!

The Adam children, Lilo, Claus and Inge, were born in Sumatra and, despite many hardships, spent their early formative years growing up in an extraordinary and unpredictable atmosphere. In 1921, however, twenty-two years after Adam's arrival in the Dutch East Indies, Adam, his wife and their children, left Sumatra for Yogyakarta, Java, arriving there shortly after the coronation of the new Sultan. The Adam family was first the guest of the Dutch Resident, Mr. Jonqui'ere: "He, indeed, was my greatest teacher of Javanese habits and customs, of Javanese arts and crafts. He gave me every opportunity to witness and photograph religious processions, wedding festivals in the palaces, ceremonies on the anniversary of the Sultan's coronation, the beautiful Serimpi and Bedoyo dances, and last, but not least, the great Wayang Wow performances on both the Queen's Jubilees, in 1923 and 1926.2

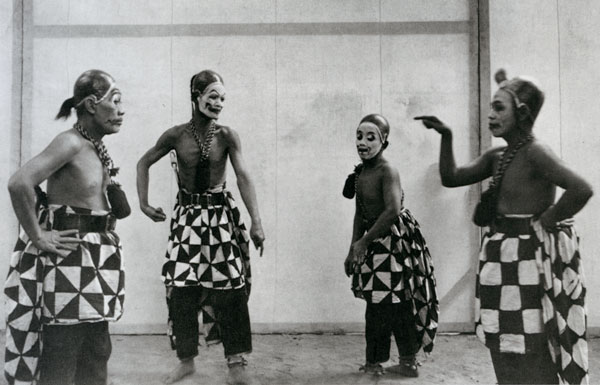

Adam established a photographic studio in Yogyakarta, and he not only did commissioned portraits but, with the express permission and benediction of Sultan Hamengku Buwono VIII, he filmed and photographed court dances and rituals. He was not permitted to use artificial light for this work, however. Radically different from the harsh conditions in Sumatra, the highly refined civilization of Javanese Court life became just as familiar to this consummate recorder of the natives of the Dutch East Indies. Adam faithfully recorded, photographed and filmed the Wayang Wong theatre, the Wayang Topeng, the Kuda Kepang (Horse Dance), the Serimpi and Bedoyo Dances and Javanese Shadow puppets.

Many of these performances were never to be repeated again to the present day. His precise verbal description of Javanese theater performances contributed greatly to the small amount of information available about this entirely different form of performing arts: "There is no stage, no settings, no curtain, no announcement of changes during the play, not even—as in Shakespeare's time—a board describing the scenery. "3

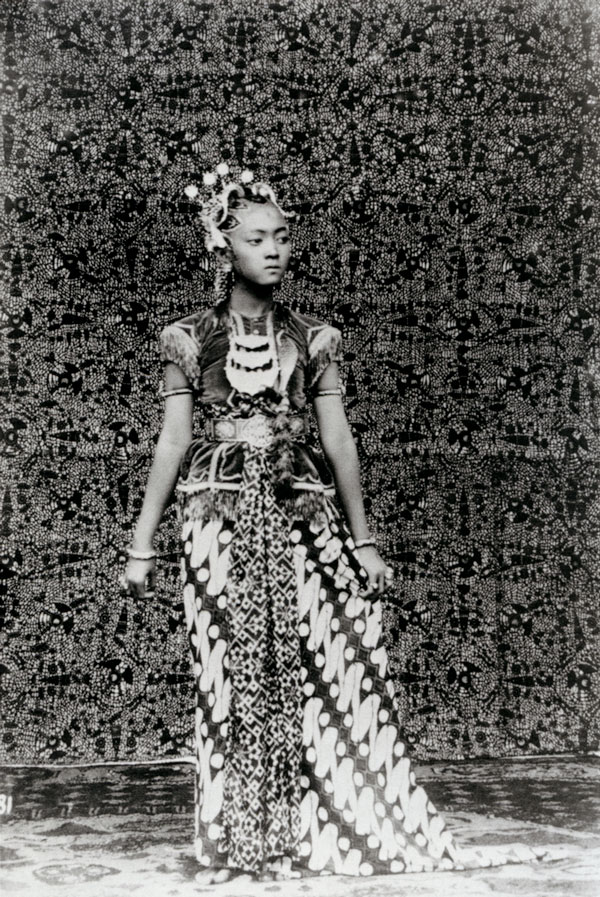

Capturing the beauty and dignity of these dancers, many of whom were of noble birth, Adam wonderfully portrayed them in their dance finery. Most of the costumes of the Javanese nobles, their everyday wear as well as their dance attire, were made of special hand-drawn batik. Adam's photographs are thus invaluable documents, since contemporary costumes are no match for their perfection.

As he had in Sumatra, Adam immersed himself entirely in Javanese life and beliefs, and he witnessed many more intimate aspects of court life in Central Java than had ever been revealed to westerners before. A prime example of this is the extraordinary photograph documenting the circumcision of a royal prince of the Susunahan of Solo, in which a white-gloved Dutch doctor protects the royal eyes while an attendant peers quizzically into the camera. It is unusual that both a doctor and a photographer would have been allowed to participate in an important ritual of the inner circle of the court.

In 1926, Adam contracted amoebic dysentery for the third time. For the sake of his own health and that of his children, the Adam family, sacrificing their deeply felt bonds to the East Indies, decided to return to Europe. He lectured in Europe, sold films and supplied pictures to German magazines. They spent some time in Salzburg, Vienna and Holland before moving to New York, where, from 1929 to 1933, Adam was curator of Oriental art at the Brooklyn Museum.

The last years ofTassilo Adam's life—he died in 1955—were spent writing for American publications and attempting to return to Indonesia. Sadly, the Javanese of Yogyakarta had lost interest in him because they regarded him as an OrangBelanda, a Dutchman. Despite his obvious love for Indonesia and its people, Tassilo Adam died far from its once welcoming shores. His collection of photographs, however, remains a tangible reminder of his presence there.

NOTES

- Tassilo Adam, "Barak Days and Ways", Asia, February 1930, 123.

- Tassilo Adam, "Wayang Wong: the Javanese Theatre", Knickerbocker Weekly, September 1943, 25-26.

- Ibid.

|

Tassilo Adam

A Sumatran Batak Sibasso priestess in a trance ceremony, 1919 |

|

Tassilo Adam

Muslim circumcision ceremony for a royal Prince, Solo, Java, 1925 |

|

Tassilo Adam

Raden Wedanan Indramardowo playing the Wayang Wong role of Bambang Semitra,, 1923 |

|

Tassilo Adam

Puteri Bibi Radjah, favorite dance of the Sultan of Yogyakarta, 1922. |

|

Tassilo Adam

Four Javanese Wayang Wong theatre clowns from the play Bagawan Mayangkara, c. 1923 - 1926. |

|

Tassilo Adam

Seven tear old daughter of Pangeran Adipati Arya Pakoe Alam VII performing the Srimpi dance,

Yogyakarta, 1925. |

| next paper | about Kunang Helmi

| contents page | asia-pacific photography | photo-web | contacts

|