|

Kassian Céphas

Side view of Borobudur, with seated Buddha,1872. Albumen print. |

Until recently, the name of Kassian Cephas, the first Indonesian photographer, was scarcely known outside a small circle of archaeologists and historians interested in Javanese culture. During the past ten years, however, several scholars have focused their attention on this remarkable pioneer and have tried to piece together the details of his life and career.

Born February 15,1844, he was named Kassian (Kasihan or Kasyian), a name with a somewhat depteciatory connotation, although it is possible for it to mean beloved or precious rather that pitiable, the most common meaning of the word.

Although Cephas' first name may be somewhat unusual, his last name is even more so. The name itself, as well as the manner in which it was acquired, reflects the social and religious background of the colonial period in which he lived and the circles in which he moved.

Little is known about his parents, but according to an oral tradition current among his descendants, he was the natural child of a Dutchman, possibly one who worked in the postal service in Yogyakarta, and a Javanese woman. Alrhough his father neglected to recognize his offspring officially, it seems that Kassian was adopted and raised by his natural father's family.

This family of staunch Dutch Protestants may well have taken credit for the fact that Kassian became the first Indonesian to be baptized in Central Java, an event that took place in Purworejo on December 27, i860. By choosing a town outside the territories of the Sultan of Yogyakarta and Susuhunan of Solo, the missionary who baptized Kassian remained in compliance with the strict prohibition against all missionary activities in the so-called Principalities, or Vorstenlanden. Moreover, by choosing the biblical name of Cephas, which is the Aramaic equivalent of Peter, the missionary complied with yet another government policy of avoiding Dutch-sounding names for converted Indonesians or Eurasians. A single name suffices for all Javanese, and it was only much later, when Cephas petitioned the colonial authorities to be granted equal status to European residents, that he expressed a wish to use his original Javanese name, Kassian, as a first name and Cephas as his family name.

In the obituary that appeared in the Dutch colonial newspaper De Locomotief '(November 18-19, 1912), it is stated that Cephas acquired his photographic skills "as a boy." In view of the minimal number of photographers active in Indonesia in whose studio he could possibly have been apprenticed, it seems likely that he began his career working in the studio of the well-known opera singer and famous photographer Isidore Van Kinsbergen (1821-1905). He is the only photographer who is known to have lived in Yogyakarta during this period. He resided there from 1863 to 1875, a time during which one would not have called Cephas a boy—unless, of course, the word was used in the sense of a houseboy.

Little is known about Cephas' early years. In 1884, when his name was first mentioned, he had already established himself as a photographer and was already the court photographer to the Sultan's keraton in Yogyakarta. It is unclear whether he had received this appointment through the intervention of his friend, the court physician Isaac Groneman, but the close association of these two men unquestioningly had a decisive influence on Cephas' career as a photographer.

In 1884, Cephas took sixteen "photograms" for a book written by Groneman on Javanese court rituals, dances and regalia. A few years later, another book by the same author described the religious festivals and the ceremonial pageants and parades held in the keraton on such occasions. Cephas again provided the photographic record that constituted the principal value of these publications.

As a court photographer, Cephas needed the Sultan's permission for such extracurricular activities; it was always requested and invariably granted. The Sultan even graciously consented to halt a parade for a moment to give Cephas an opportunity to photograph the procession. The documentation that Cephas was able to provide of the ceremonies performed in the keraton is virtually unique and of immense importance to our knowledge of late nineteenth-century Javanese cultural history.

In 1885, a group of Dutch residents founded the Archaeological Society of Yogyakarta. In that same year, its first president, J. W. Ijzerman, discovered the hidden base of Borobudur, with its reliefs illustrating the Karmavibhanga. As the processional path that hid these reliefs from view was dismantled, section after section, Cephas was commissioned to photograph all 160 reliefs before they were covered again. This complete record has remained until today the sole source for the study of these reliefs. Seventy years later some of the original negatives could still be used to make prints, but since that time they appear to have been lost or destroyed by moisture and mildew.

The second president of the Archaeological Society of Yogyakarta was Dr. Isaac Groneman, and it was during his term of office that the Society embarked upon its best known, but least appreciated activity: the drastic "cleaning" of the ruins of Candi Loro Jonggrang at Prambanan. By removing the detached stones from the central courtyard of this temple complex and throwing them all on one large pile, the over eager amateur antiquarians created an additional burden for the next generation of archaeologists who faced the task of restoring these monuments to their original glory.

Groneman's controversial involvement in this ill-advised venture had one lasting, positive result, his book Tjandi Parambanan op Midden Java na de ontgraving (Candi Prambanan in Central Java After the Excavation). Again Cephas provided the most significant part of the publication, its sixty-two photographs of the temples of Prambanan and the Ramayana reliefs of Candi Siva. This painstakingly accurate and comprehensive record was of considerable documentary value to the restorers of these temples and their reliefs.

Cephas' putative teacher, Van Kinsbergen, had an outgoing personality and an artistic temperament. The native photographer, on the other hand, was more of a quiet force behind the scenes, a self-effacing Javanese. Even when he actually made an appearance, it was in an inconspicuous, unobtrusive manner. In one of his phototographs of the north side of Candi Siva, the man standing in the doorway of the cella is none other that Cephas, himself—fifty years before Alfred Hitchcock. In all probability, his son Sent, who was to succeed him as court photographer, opened the lens for this image. Cephas also appears in several of his photographs of Borobudur.

The last recorded involvement of Cephas in matters concerning Javanese antiquities dates from 1902, when he alerted the authorities to the recent theft of sculpture from the Candi Plaosan, noting that tracks made by the wheels of the thieves' cart were still visible. It is likely that the object stolen was the beautiful head that was to appear in the Ny Karlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen in 1907 and that, at the present time, can no longer be located in the Danish national collections, to which it was transferred seventy years ago.

When we compare Cephas' oeuvre with that of his teacher, Van Kinsbergen, we cannot help noticing a marked difference in approach. Van Kinsbergen was highly idiosyncratic in his selection of themes and subjects. He appreciated the beauty of ancient Javanese art, and he photographed what he liked with no apparent desire to convey to the viewer an overall impression of the monuments. But his magnificent photographs of the reliefs of Borobudur even inspired Paul Gauguin, in whose paintings and wood carvings the figures portrayed by Van Kinsbergen appear time and time again.

The value of Kassian Cephas' work resides first and foremost in the faithful record it provides of monuments and antiquities, of court nobility and ceremonial life in the keraton. Cephas was a man of two worlds. As an official of the Sultan, he became familiar with the language, protocol and traditions of Javanese court life. As one who had achieved equal status with European residents, he moved in their circles as well, equally at home speaking either Javanese or Dutch.

Conscientious and fully aware of the importance of permanent records to posterity, he recorded what he saw as meticulously and completely as would an archaeologist. In this respect, he was far ahead of his time.

|

Kassian Céphas

A young female abdi dalem servant to the royal courts of the Sultan of Yogyakarta

posed in a studio, 1880. Hand-colored photograph. |

|

Kassian Céphas

Bedoyo Prabu Dewa dance, Sultan Hamengkubuwono VII's palace, Yogjakarta, c.1880. |

|

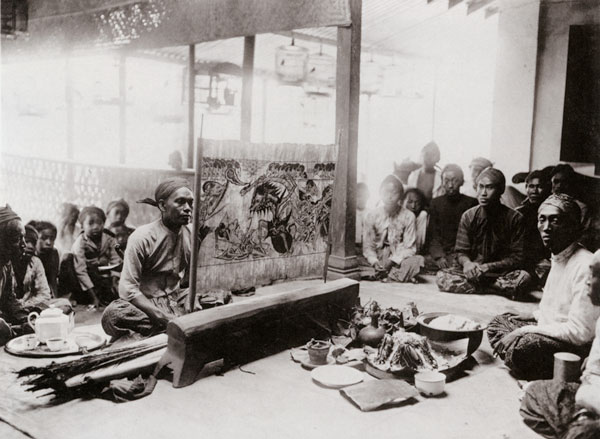

Kassian Céphas

Wayang Beber from the village Gelaran near Wonosari, Central Java, 1902 |

|

Kassian Céphas

Overview of Borobudur from the northwest, before restoration, 1872. |

|

Kassian Céphas

Man climbing the front entrance to Borobudur,1872. |

| next paper | about Jan Fontein

| contents page | asia-pacific photography | photo-web | contacts

|