|

Henri Cartier-Bresson

Sumatran rice fields, 1949 |

Long before great religions, aggressive merchants and committed ideologues began to shape modern indonesia, a host of cultures and communities developed refined adaptations to the island world of equatorial southeast asia. almost without exception, the peoples of the indonesian islands speak tongues of a single language family (austronesian), share common environmental and spiritual concerns about rice agriculture and possess elaborate craft and art traditions manifested in architecture, carving and textiles.

These cultures became established in seacoast and mangrove coastal areas, successfully farmed deep into the inland rainforest and consistently produced significant surplus rice crops on expansive inland plains that were often fertilized with cyclical showers of volcanic ash. Common themes of culture, subsistence agriculture and language bind the peoples of this vast tropical archipelago together despite the wide dispersion of ethnic groups across thirteen thousand islands.

The cultures of Indonesia developed over many millennia of migration, adaptation and cultural evolution. Throughout the archipelago, island cultures are marked by hoary myths of origin and ancient lore of migration. Many such stories recount ancestors' departures by sailing craft, recall their perilous sea journeys and mark their first landfall and settlement of harbors, valleys and hillsides. In many cases, unusual stones, deep springs and great banyan trees mark the place of first settlement where progenitors—today often elevated to the rank of deities—are thought to have erected the first clan house and farmed the first cultivated field.

Such myths of original settlement are frequently enhanced by tales recounting the first planting of sacred seeds from which subsequent crops of rice are thought to have descended. Notions of the goddess of rice, a figure most graphically depicted in a plethora of folk arts, are common throughout the region. These depictions range from abstract designs carved on bamboo offering platforms to living Balinese tapestries fashioned from the supple leaves of the sugar palm to intricate designs incorporated into the ikat fabrics of the eastern Indonesian islands.

Ecology, economics and history have combined to create a significant distinction between the core, inner-island regions of Java and Bali and the peripheral, or outer-island regions that cover two-thirds of today's Indonesian national territory. The fertile volcanic soils of Java and adjacent Bali have enabled rice agriculture to flourish, and populations there have expanded. On Java, the influence of traders and religious teachers from India was most pronounced in the 1200s, when contact was first made by Indian traders sailing east through the Java Sea. Monuments standing in the cool mists of the Dieng Plateau, in central Java, attest to this earliest impact of Hinduism. Local rulers validated and enhanced their power by their association with traders and Hindu teachers from across the seas. Literacy was acquired, first in Sanskrit and subsequently as a result of centuries of Indian influence. A distinct Javanese script was also developed, one of the many profound consequences of the coming of Hindu civilization.

The subsequent emergence of precolonial kingdoms and trading states on Java and Bali and along coastal Sumatra reinforced the distinction between center and periphery in Indonesia. The impact of great kingdoms such as Mataram and Madjapahit extended not only throughout Java, but overseas to outlying regions as well. Court regalia surviving in locales such as South Sulawesi, eastern Sumatra and southern Kalimantan (Borneo) attest to the degree of commercial intercourse and cultural contact between rulers of the outer-island, non-Javanese kingdoms and the powerful states of the center.

Alphonse de Albuquerque, the indefatigable Portuguese explorer and adventurer who searched in vain across the wilds of northern Mexico for the fabled seven cities of gold, was the first European to make an impact in Southeast Asia. In 1511, Albuquerque's fleet engaged the Sultanate of Malacca on the west coast of the Malay peninsula in a deadly struggle for control of a rich trade in spices and silks. Many of the riches of island Southeast Asia were brought to Malacca, a flourishing Muslim coastal city, sold thete and transported either north to the coast of China or west to India, the Levant and ultimately Europe.

Albuquerque's defeat of Malacca presaged first the compromise and then the annihilation of independent island states in the region. The intrusion of European forces opened the way for western trading companies to establish alien monopoly control of local economies by force of arms; and, over time, firms such has the Netherlands East Indies Trading Company not only conducted trade, but increasingly governed through an elaborate system of administrative control.

In rhe sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Dutch traders dominated and developed their capital of Batavia, on the notthwestern coast of Java; but, as Dutch influence spread rhroughout the island, it was confronted by a powerful and intrinsically hostile counter force, Islam. In the three centuries preceding the arrival of Albuquerque in Southeast Asia, the ideological and moral force of Islam had wrought fundamental changes throughout the region. Islam entered Indonesia by way of coastal India, first making its impact on trading ports of western and northern Sumatra, slowly spreading throughout harbor cities and trading centers.

By the mid-fourteenth century, the great kingdoms of central Java had embraced Islam, although with somewhat less fervor than was true in northern coastal regions. By the time the first Europeans sailed to Java more than two centuries later, Islam was already well established. As European influence in trade and administration deepened in the fitst centuries of colonial rule, Islam increasingly became the rallying point and major counter-force for traditionalist, irredentist and proto-nationalist forces opposing the intrusion of foreign control of the area. Paradoxically, the fanatical commitment of intrusive European powers to engage Indonesian Islamic forces often led to the extension of this faith into areas of the archipelago that had been unaffected by the teaching of the Prophet Muhammad prior to 1511.

The extension of Netherlands East Indies conttol over the region was a long and fitful process that extended from the early sixteenth century to the first decade of the twentieth. In the early centuries of Dutch commercial intercourse with coastal trading states, competing British, Portuguese, Spanish, French and even Danish powers made an impact on selected regions of Indonesia. Dutch trading acumen, diplomatic skill and persistent interest ultimately allowed the Netherlands to prevail. The political and cultural coherence that gives form and substance to the term Indonesia hardly existed in the early years of Dutch influence in Java and Sumatra, however. Warring sultanates and fiefdoms were slowly brought under Dutch control, mostly by the device of inditect rule, in which honors, monies and superficial administrative privileges were bestowed upon native

rulers in exchange for monopoly trading privileges.

For over two hundred years, Dutch interests in Southeast Asia were represented not by the crown but by the Netherlands East Indies Trading Company. Representatives of this consortium of trading firms developed Batavia as a port and center of commercial activity, outfitted private navies and armies and slowly extended their influence across Java and Sumatra and into the far-flung outer-island regions. Only with the dawn of the nineteenth century was the influence and prestige of this trading company supplanted by that of the Netherlands East Indies Government.

The Dutch were content to rule through local regents. They assembled competent armies officered by Dutch professionals but staffed largely by minority outer islanders who had no intrinsic loyalty to the increasingly compromised courts of coastal and central Java. An export economy was established in which crops such as opium, sugar, indigo, coffee, cloves, mace, nutmeg, rubber and copra were nurtured, assembled and traded through monopoly control to advance the cause of the Company first and then the Dutch government.

The village economy was fundamentally altered by the interests of the occupying Europeans. Javanese farmers, for example, were often forced to cultivate sugar, thereby reducing their ability to expand rice and food crops on their lands. Sumatran villagers were encouraged to work on rubber plantations; and, when they proved unequal to the task, laborers from more densely populated Java were imported to secure adequate production.

The extension of Dutch control over the East Indies was to some extent an unplanned process. Their intrusion as a technologically superior foreign power into local politics shifted the indigenous system of political alliances, radically altered patterns of intra-island and international trade and invested a new superordinate expatriate elite into the previously highly stratified social world of Java. The Dutch were content to leave the great majority of the native population in traditional village locales, and only select members of the noble elite group were educated in urban Dutch-language schools in preparation for subordinate roles in the colonial bureaucracy.

European colonial governments in tropical Asia ultimately foundered on the fundamental paradox of indirect rule. Because the number of Dutch colonial officials and expatriate residents in the Indies never amounted to more than a fraction of the indigenous population, considerable human resources had to be managed domestically to ensure the functioning of the colonial state, economy and society. By the dawn of the twentieth century, the first students from the Indies were on their way to Europe to undertake advanced training in the Netherlands.

This handful of young Javanese and Sumatrans was exposed to the currents of contemporary western history at the same time that significant nationalist sentiments were coalescing among Muslim and secularist-nationalist groups sequestered deep within indigenous village society. Revolts and rebellions were constantly confronted and suppressed over the centuries of colonial rule, yet the spirit of independence and rebellion was never thoroughly quashed by the Dutch. Few such movements, which were largely nativistic insurrections against alien control, presented serious challenges to European authority.

|

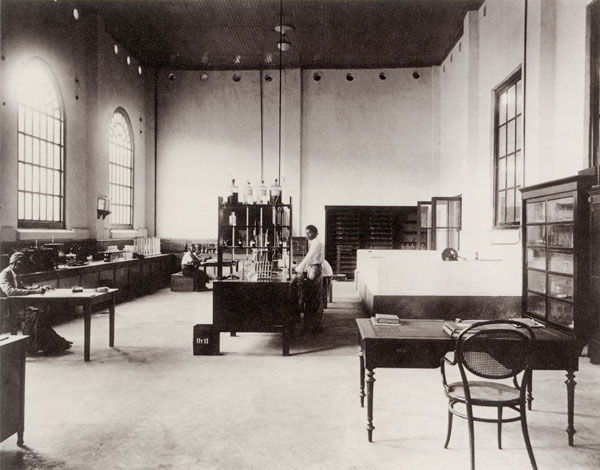

Onnes Kurkdjian

Laboratory of the Dutch Djatinroto II sugar factory, East Java, 1924. |

In the twentieth century, the western-trained Indonesian intellectuals joined with village-based social, cultural and religious organizations to give birth to an unprecedented nationalist movement that ultimately succeeded in restoring indigenous control to the archipelago. Forging a nationalist movement in the face of active hostility from a colonial government is difficult in most circumstances. Indonesian nationalist leaders were faced with the task of creating a national entity out of a multitude of distinct cultures that had never in the past been truly unified under one political banner, had never shared a distinct common language and had rarely succeeded in bringing more than a few dispersed island kingdoms under unitary rule. Nevertheless, there were historical precedents and cultural norms that facilitated the process of national union.

The great Javanese kingdom of Madjapahit had brought states in Sumatra, Borneo and Sulawesi under its overlordship centuries before the Dutch appeared on the scene. Traders emanating from ports in eastern Sumatra and the Malay Peninsula had succeeded in implanting their language as a lingua franca throughout the Indonesian islands. The very fact of Dutch colonial control, which by 1906 extended from Aceh in northern Sumatra to western New Guinea, enhanced the patriotic consciousness of Indonesian nationalists. Wotking against the national movement was the ease with which the colonial government had been able to manipulate indigenous ethnic antagonisms to Dutch advantage.

Despite suppression by the Dutch, the nationalist movement grew in the early decades of the twentieth century. Marxist, Muslim and secular nationalist ideologies accommodated alternate views of the world. Javanese, Sumatran and a host of minor ethnic groups set aside ancient antagonisms and accepted the goal of forging an anti-colonial independence movement. A national language, based on Malay, was adopted in the 1920s. Modern nationalist organizations developed and intermittent revolts erupted, but it seemed that not even these advances could impact the mystique of European invincibility in the Indies.

Within weeks of the outbteak of World War II, however, the myth of colonial destiny that the Dutch, British and French had carefully nurtured over the centuries in Southeast Asia was destroyed. Japan moved into the Netherlands East Indies shortly after Pearl Harbor; and, by mid-1942, all Dutch forces had been defeated and Dutch nationals were relocated in concentration camps manned by Japanese soldiers.

Occupying Japanese forces made good on pre-war promises to train Indonesians in military arts. By the end of the war, the Japanese had exported tens of thousands of forced laborers from Java to work sites across Southeast Asia. Few such romusha returned from the labor camps, although, with the exception of Irian (West New Guinea) and the northern Moluccas (Morotai Air Base), little actual fighting transpired on the ground in Indonesia.

The Japanese land armies were virtually intact at the end of the war, and many Japanese soldiers turned their weapons over to Indonesian cadets. Indeed, Japanese military leaders encouraged Sukarno, the first ptesident of Indonesia, to declare independence prior to the Japanese capitulation in Tokyo Bay.

The surrender of Japan ushered in a bitter period of prolonged warfare in several former colonial regions of Southeast Asia. In Indonesia, the Dutch attempted to reclaim their colony by force of arms, sailing on British warships from safe haven in Australia in the weeks just after the Japanese surrender. In November and December 1945, in the city of Surabaya, British and Dutch troops engaged in bitter armed clashes with Indonesian nationalists who were determined to defend their newly independent homeland. The Indonesian revolution lasted for nearly five years, ending in the last weeks of 1949 with the transfer of sovereignty from the Netherlands to the independent Republic of Indonesia.

The artistic heritage of Indonesia encompasses almost all traditional arts known to man. Depictions of daily life are found on woven leaf tapestries, in designs etched in wood and on textiles embellished by means of painting, batik or ikat dyeing or embroidery. Sculpture in clay, rice paste, wood and stone and casting in bronze and precious metals comprise yet further dimensions of the imaging of Indonesia in the context of traditional village culture. The many cultures of Indonesia, ranging from the high civilizations of the Hindu-Buddhist courts of Java and Sumatra in pre-colonial times to small bands of hunters and gatherers that still persist in the rapidly diminishing rainforest have long fashioned images of the environment, man, domestic animals and the supernatural with materials at hand.

Although photography entered Indonesia from afar and was borne necessarily on the wings of colonial enterprise, it has also contributed to the process of the imaging of Indonesia. The power of photographic images was immediately recognized by Indonesian rulers and petty princes who, early on, commissioned porrraits of their families and courts. Photography also became an important medium for the validation of the colonial enterprise in the Netherlands as popularly oriented Dutch-language publications extolled the virtues of European administration while exploring the cultural and geographical diversity of the great tropical archipelago.

Toward Independence concludes with photographs by Henri Cartier-Bresson taken as Indonesia emerged from colonial domination some forty years ago. Since that time, photography in Indonesia has, as elsewhere around the world, taken root as an essential element of daily life. Few major life crisis rites, be they weddings, circumcisions or funerals, transpire in Indonesia today without being recorded photographically by professionals or family members. Indeed, indigenous video specialists in Bali and in Tana Toraja have become a new and essential element in the planning, budgeting and documentation of major traditional rituals.

Images of Indonesia expressed in traditional arts such as incised wood, woven leaves, ikat textiles, painted panels and sculpted stone reflect indigenous perceptions of the universe. Early photographic images of Indonesia reflect Eurocentric visions of colonial society. The photographs presented here conclude at a point in modern Indonesian history when the legacy of the colonial past was receding and nationalistic perceptions of the present were coming to the foreground.

| next paper | about Eric Crystal

| contents page | asia-pacific photography | photo-web | contacts |